Born and raised in Tampa, Florida, self-taught watchmaker Ernest R. Tope learned the ropes first through helpful watchmakers willing to pass on their knowledge and later honed his skills as the resident watch repairer at a Florida jewelry shop for twelve years. First studying and practicing watch repair, then later as a Factory Trained Rolex Technician.

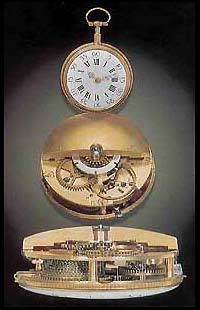

Like most future watchmakers, Ernest's curiosity began when he was young and helped foster his interest in all things mechanical. With a varied work history, Ernest settled into life as a watchmaker repairing standard watches, but also taking on such challenges as a watch with an ivory movement, a minuscule Patek Philippe hunter case pocket watch as well as an Hamilton 992E with Lucite plates--far beyond the usual skeletonized movement.

His education has brought him in touch with Henry Fried and his work has included, Breguet, Audemars Piguet and Chronoswiss.

Curious? Then read on and enjoy.

PR: So, let's start off with the basics; how old are you and where were you born and raised?

ET: I was born in Tampa, Florida in 1951 and grew up there for most of my life.

PR: Where were you trained in watch repair? What was that like?

ET: I received no formal education in watch repair. Mostly I learned by applying my experience in life with reference material and what I could garner from other watchmakers. Fortunately most watchmakers I know are willing and sometimes eager to share knowledge. Much written material exists and is usually a very reliable source for the basic concepts. The American Watchmakers-Clockmakers Institute has been instrumental in providing current wisdom.

PR: What was your first professional position and with whom?

ET: My first position was with a small independently owned jewelry store. There I began to learn the watch repair trade that went along with the skills I had studied.

PR: How did your childhood education, or experiences affect your decision to enter Watchmaking?

ET: Many a watchmaker dismantled their toys to see how they worked. I was no different. I learned to love mechanical things and focus on how they functioned. Eventually it was this love for mechanical things that drew me to watch restoration as a vocation. I still love discovering a mechanism of which I am not familiar.

PR: What did you do before becoming a watch repairer?

ET: I had been a Motorcycle Mechanic, a Firefighter and a Cabinet Maker not to mention a few other endeavors.

PR: Any idea what your old school friends are doing these days?

ET: I know what a few are doing. But your question has made me realize that I haven’t kept up with most of them. As I grow older I see that I was not inclined to keep long term relationships with more than a few special friends. Wonder if I’m missing anything.

PR: Are you a watch repairer, or a watch maker? Do you see a difference in these two terms, or occupations?

ET: Semantics for the most part, the term watchmaker implies to me those who work with watches. There are all levels of skills and applications that are covered under the same term. If you want to understand how the industry delineates these skills, you could examine the Official Standards and Practices for the Preparation, Education, and Certification of Twenty First Century Watchmakers. This can be found on the web at:

http://www.awci.com/documents/June2006sandpforwatchmakers.pdf

Some feel that true "Watchmakers" should be able to make a watch from scratch. I think they should be able to competently service a fine watch without damaging or degrading it in any way. That takes a certain level of skill, knowledge, and integrity with ethical standards. I have been doing that for a long time now.

PR: What was the first watch you owned? Do you still have it?

ET: Absolutely not, actually I remember leaving it on the back bumper of the family car while I was playing. My Mom drove off and I never saw it again.

PR: What was the first watch you ever repaired, either professionally, or before?

ET: It was an old Studebaker pocket watch. Not worth much and not much confidence.

PR: Any opinion on the decline that mechanical watches and Switzerland in particular, saw during the sixties and seventies?

ET: No real opinion.

PR: Was it the fault of the Swiss makers, or the cheap, accurate imports that entered the market? Who is to blame for that downturn?

ET: It was in the stars my friend.

PR: What do you think fostered the upswing in the eighties?

ET: It was brilliant marketing on the part of geniuses.

PR: How did the downturn and upswing affect your business?

ET: I became a bench jeweler because of the rumors and forecasts of various speculators. I returned to Watchmaking in the later eighties because I landed work at an Official Rolex Dealer. From then on it has been watches only.

PR: How do you feel about the ever increasingly complicated watches we're seeing these days?

ET: I like it because servicing them is my specialty. I am concerned at the number of beautiful and valuable watches that receive inappropriate treatment by the uniformed. Every watchmaker of high caliber complains of seeing watches that have been abused. The fastest way to demolish a fine complicated watch is to put it in the hands of the unqualified. I think there will be a great shortage of qualified people to service such fine mechanisms. Only when the owners become savvy in knowing who is qualified will they be free from that threat.

PR: Do you feel these will be a boon to new watchmakers, or a hindrance with their highly technical nature?

ET: Both, they will be more expensive (time consuming) to service and more subject to abuse (inadvertent damage). On the other hand, the owners who enjoy them are willing to pay for competent service and are delighted when the watch performs well. That means the competent watchmaker would have plenty of good paying work.

PR: How did you first learn about the American Watchmakers Institute? How long have you been a member?

ET: I joined when I learned of it in 1984. A fellow watchmaker invited me to a local gild meeting and educated me about the organization. I’ve been a member ever since.

PR: Do you have a mentor, or a watchmaker you hold in high regard?

ET: There are many but I suppose the guy that sticks out is the late Henry Fried. I learned from his books and later had the opportunity to spend a little time with him. He was amazing and a giant role model for the Horologist.

PR: Where do you see the watch repair business heading?

ET: It will be interesting to watch. I am not sure how the independent repairer will be supported by industry. As long as they are there will be some. Factory service will always be challenged to keep up with service for the large numbers of watches being

sold.

PR: Will you be going along for the ride, or will you go on to other things?

ET: My work is not the mainstream. I repair and restore watches that others do not. This is an area where there is no industry support to rely upon. I have more restoration work than I can do. You might say I am independent of industry. Lately I have been toying with making unique watches and admit I am drawn to that possibility. There will be more on that in the future.

PR: Are you where you pictured yourself as a young man, work wise?

ET: As a young man I thought I would have to work to survive. Now I know I can thrive without working. I never thought making money would be so much fun.

PR: Where do you see yourself in ten years?

ET: Independent Horology, designing and making unusual watches.

PR: Do you have a favorite maker, or watch company?

ET: I could declare a favorite but actually it keeps changing depending on what marvel comes across my bench. Some of the finest watches I have seen were not signed. Anonymous was the most prolific watchmaker. Can you imagine a watch sold today without a makers name on it?

PR: When not at the bench, how do you spend your time?

ET: Self-discovery, I am on a great journey to know and love myself. This requires much self-observation and meditation. Freeing myself of the constraints of my past is a great pastime. I have no big hobbies or boy toys, just a big delightfully interesting world to be part of.

PR: What was your most difficult project, either difficult because it was complicated work, or just plain hard and nasty?

ET: The biggest challenge so far was making a spring detent for an English pocket chronometer. I may have found something harder now. Currently I am making an escape wheel for an extremely small cylinder watch. The wheel is 2.8mm in tooth diameter and .25mm high. It must be easy; the original was made before electricity came into popular use.

[Editor's note: Here is a link to a website discussing a spring detent]

http://www.historictimekeepers.com/Detent.htm

PR: What was your easiest project?

ET: Can’t remember.

PR: Are you a "strap and battery" repairer, or do you turn your nose up at that sort of watch repair work?

ET: I still do that stuff for my friends.

PR: What is the silliest question a customer ever asked you?

ET: How often should I wind my quarts watch?

PR: Are watch repairers a cloistered lot? Are "outsiders" welcomed?

ET: There are all kinds but I find most friendly and willing to share information to those who respect their time. They may not welcome others who ask many questions instead of dong the research. It’s like asking for a free appraisal and historical evaluation on the back of the repair envelope. I have been bugged excessively for explanations to the novice. Try that with your lawyer or auto mechanic and see what happens. Generally, watchmakers are much nicer when they tell someone to get lost. When adequate respect for time is apparent most watchmakers will welcome anyone.

PR: What advice do you have for people like me, who wish to make this a new career, or a hobby?

ET: Research, Research, Research, and be real about your ability. The largest impediment to achieving success is a poor attitude. Give yourself full credit for what you know and acknowledge there are multitudes of things that you do not know. Discovering those things is a great adventure.

PR: What is your best kept secret, or tip for repair work?

ET: What goes poorly today may go miraculously tomorrow. Emotional stability and a sense of opportunity in whatever is happening serve me well in my work and my life. Now don’t tell anybody or...you know.

PR: And lastly, ties: A single Windsor, or a double Windsor knot?

ET: I do not like to wear one. When forced I like one of those clip on ones from the 70’s. When there is absolutely no choice in the mater I will use a Windsor. Never heard of a double Windsor. Must be a different culture.

I'd like to thank Ernest for taking the time to participate with this interview. The experiences Ernest has not only encountered, but sought out are proof to all of us interested in Watchmaking, that it is possible--whether success, pleasure with our work, or fixing the hither to believed unfixable. Thank you, Ernest.

If you'd like to contact Ernest to inquire about his services, please visit his website at:

http://www.watchrestoration.com/

Email at:

watchmaker@watchrestoration.com

Or call:

(813) 505-9749